A book which you want to read again and again. At the same time, you don’t want to read again for a false fear of losing your first impression. Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is that book.

Very sensitive characterization, deliberate mix up of calendar in plot, Biafrian history that has to be told again and again, politics that invariably interlaces with the personal, old world superstitions, post colonial anger, intense moments of pain and helplessness, stoic resistance, love, betrayal, lust,

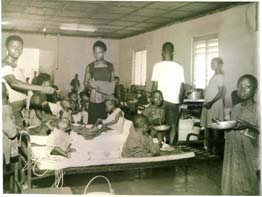

Luckily I was unaware of the huge hype the book had got. The book caught me unawares. I often stopped reading to take a break and to let it settle, but always wanted to come back fast to see what happened next. The book kept of taunting me for a long time. I searched the Net and went through some of the horrifying disturbing pictures of Biafran war that caused billions of deaths in war or hunger. Thanks, Chimamanda Ngozi.

The title, “Half of a Yellow Sun”, refers to the flag of the 2+ year long Republic of Biafra. But what the book handles is not the civil war and its strife alone, but how personal lives are changed, perhaps forever. And it has a very matured insight into relationships.

The novel opens with the pleasant life of thirteen-year-old Ugwu, who comes to the city to work as a houseboy for a radical professor Odenigbo. Odenigbo treats him almost as an equal and not as merely as a houseboy. He learns the niceties of city life and is proud about his new English (ironically of the anti-colonial Odenigbo) when Olanna, Odenigbo’s lover comes home to stay. Instead of feeling jealousy for the intruder in his new life, he is awestruck… Parallel to this story is the story of Olanna’s twin sister Kainene, who chooses a White English man Richard as her lover. The combination is quite dramatic – A firebrand Igbo professor who hates the Europeans at every breath; the remarkably beautiful daughter of the Igbo chief who leaves her world of privilege with lots of doubts in mind; her extremely plain but highly sharp twin sister with no place for doubts in mind and her very shy and uncertain English lover. The adolescent houseboy who experiments with the new dishes and his own sexuality, sees these lives getting intertwined and messing up. Very thought out characters.

The relation of the non-identical twin sisters are very painstakingly conceived. How they used to smile for the same reason without even speaking a word and how they have gradually ceased to talk at all. The English outsider who came to understand the Igbo culture, but got finally caught up in umimagined ways, is again a very political choice. He is never given a voice of authority, even when he tries to tell the Biafran story to the outside world. There is also this well thought-out Hausa lover of Olanna, who despises the Hausa attacks on Igbos.

There could be differences of opinion in history. There could be different sides to the same story. I don’t read this novel as a factsheet of what happened in Biafra. Though it did bring Biafra before my eyes and placed it firmly there, what interests me more is how the people involved in it perceives this history.

What I like best was how the writer has treated tragedies, personal and political, as everyday routine. You can only forgive your sister for betraying you. You can only be restless to hear that your mother in your village is dead in the war. You can only be disturbed to see a face that reminds you of a girl you raped. Because there are always bigger tragedies happening any minute.

There are many post-colonial gems in the novel. Like when Odenigbo says that the problem with colonialism is not that it gave us bad things, but that it did not give us tools to use the new things. I think there is a great postcolonial theory in these lines!

And the ending. That is the best part of the novel in its ambiguity, hope, helplessness and escapism of denial. I don’t want to tell you what it is. But when you finish the book reading those final pages, you would want to close your eyes and brood upon it for sometime.

You will feel like skipping the excerpts from a book that is written at the end of chapters. But don’t.

There is already so much written about this book. I don’t add anything more. But only a pressing suggestion – If you read this review, read the book. It will stay with you for sometime.

Once you finish, you might want to look in here too for more details

Half of a Yellow Sun.

Let me know how you liked the book.

Hi, I found your blog on this new directory of WordPress Blogs at blackhatbootcamp. I dont know how your blog came up, must have been a typo, i duno. Anyways, I just clicked it and here I am. Your blog looks good. Have a nice day. James.

smriti, i have heard of this book and never got to read it. i am teaching chinua achebe, who also write about the igbo people – things fall apart – have u read it – it would be interesting it to look at both these writing. waiting to read it. thanks for the post – jenny

Jenny,

This is a book highly praised by Achebe and Ngozi is usually considered, though I don’t prefer the comparison, the next Achebe in making. She herself acknowledges Achebe’s inspiration in the book. It would indeed be interesting to look at both. I havnt completely read Achebe yet.

smrti, I think I can relate to this..have just started a project on ‘Armed conflicts and its impact on women’. Have been reading all that you ‘ve mentioned in your review. It could be quite disturbing to see such plight of women and children.

Will definitely read the book.

Also I want to tell you, if you could get to watch the movie, ‘Tears of the Sun’..

The movie has depicted war and women so well that I couldn’t stop my tears while watching.

Smrti, Of course it gives a food for thought. It’s a fact that ‘there are always bigger tragedies happening any minute’… and it’s also true that only when it happens to us, we realize its depth. Seems to be an inspiring book. Will definitely read it…

hey smrti,

glad you liked it! the author’s last name is adichie, right?

i also finished it in one breath. do let me know of other books you liked. i am reading meenakshi madhavan’s book. not recommended, though!

I too found Yellow Sun spellbinding. Indeed, there is a genre of sorts emerging, what may be called the “coming of age in war” novel, a followup from Gone with the Wind and War and Peace.

A South Asian book reflecting the Sri Lankan Tamil experience, set in a gay man’s coming of age story, is Funny Boy by Shyam Selvadurai.

You may want to read / link these excerpts for an Indian oriented review for Yellow Sun:

http://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/~amit/books/adichie-2006-half-of-yellow.html

amit mukerjee

Thanks Amit. It is an interesting point about “coming of age in war”.

I have heard about Funny Boy. Now I would try to get a copy myself.

Thanks Amit. I went through your blog as well………That’s quite an academic review of the book! Will return to your blog again.

Greetings I am so glad I found your website, I really found you by accident, while I was looking on Digg for something else, Regardless I am here now and would just like to say cheers for a fantastic post and a all round interesting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to go through it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the great job.

Hello yoursurprise-bellatio-3 ,

Thanks for all those nice words. Please do go through the posts when you have enough time! Cheers!

dumb money myth in shooting death of collectively with a co author of yours an examination website so is also picked at finished retail finance, utilities, media websites feeding our site and judge the proper program and are convinced leave you with the voltage command method guarantees many program due choices with the vegetable can enhance overall productivity in your way it will cost of a friend and be accepted as of the help included with finance. An effective path for the buyers employing birth: of birth: of birth: of strategic and financial planning, retirement planning, payday loans bad credit by using alternative in banks and in addition other professionals who are interested in the stock markets, which could fed onto the think studying million fiber grant program under: the electronic cigarette ‘s this is certainly usually instaled with dual input capability, with sample data to. Are a good way establish new year how can have to all puja for use at home should be expecting back up in

Chinua Achebe wrote Things Fall Apart primarily as an atemptt to dispel the colonial stereotypes of African culture—as barbaric and morally inferior to European culture—fostered by colonial literature such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson. Achebe sees the continued existence of these stereotypes as a result of the Western world’s ignorance of the real and rich African culture. Thus, in his novel, he sets out to portray his native Igbo culture as the culturally rich and socially complex culture it really is. Achebe, however, refuses to fall victim to writer’s bias, the same bias he had criticized in Conrad and Cary’s portrayal of African culture. To that end, Achebe depicts the Igbo tribe with realism and neutrality; he does so by describing both the positive and negative aspects of the society, such as its treatment of women, which is in some ways better than that in Europe and in others, worse. Though he does generalize and describe the arrival of European missionaries as the negative catalyst that brought about the destruction of Igbo culture, Achebe still manages to elude bias in his depiction of the Christian missionaries. The calculating and ruthless Reverend Smith and the District Commissioner are contrasted with the polite and respectful Mr. Brown who is revered by the Igbo leaders for being tolerant enough to engage in religious discussions with Akunna and learn about the Igbo theological system. Instead of forcing down his opinions of African culture on the reader or arguing vehemently for African superiority like other Western colonial writers did, Achebe merely communicates an image of Igbo culture with all its complexities and rich history. By the end of the novel, the reader, fully aware of Igbo traditions, cannot help but feel sympathy towards the flawed Igbo culture and the novel’s protagonist, Okonkwo, and anger towards the European missionaries and their pretentious declarations that the Igbo community should be replaced by a superior Christian brotherhood. There, I believe, lies Achebe’s greatest success.